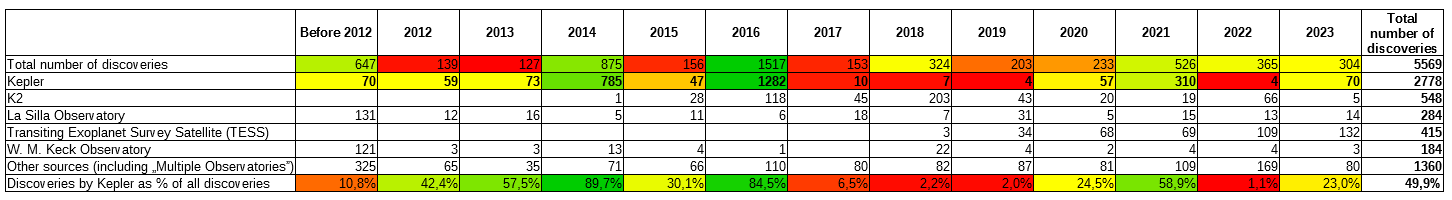

So, I looked deeper at the data, and as I suspected in my previous comment (and my wife knew it already) behind the outlier results in 2014 and 2016 was one specific mission: Kepler space telescope. Kepler was responsible for the discovery of 90% of exoplanets discovered in 2014 and 85% of the discoveries made in the record year 2016. It was also responsible for 49,9% of discoveries of exoplanets in the dataset.

What is important, Kepler was retired by NASA on October 30, 2018 after it ran out of fuel. In the dataset, we can still see discoveries of exoplanets attributed to Kepler after 2018 - even last year (70 discoveries, we can say it was a good year for Kepler), but the numbers are lower now (2021 was still the third-best year for Kepler) with an irregular downward trend. I assume that the discoveries were made in later years based on the analysis of images previously collected by Kepler.

Its mission is continued by Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) since 2018, but it was not that effective as Kepler, but it seems to be getting better over the years. See my table below with the most efficient projects/observatories over the years. Relative formatting is applied to each row to show changes over time.

Kepler might still be a source of a substantial number of discoveries of exoplanets this year (last year it was 70), or it may bring little to the total number (in 2022 it was 4), but we should not expect numbers like in 2014 or 2016 from it. Based on that, I am further reducing my probability slightly to 56%.

My thoughts: Base rates and Laplace rule are useful for forecasting, but if the causal mechanics/driving forces behind the numbers change, our expectations should also change. But this correction, of course, becomes subjective, and may make us even more vulnerable to the influence of biases. See a great comment about that by @ctsats : https://www.infer-pub.com/comments/121097

Bear in mind there's two operations involved in finding exoplanets:

Finding candidates, which is highly random. Occasionally something like a stellar transit will occur, which means the candidate is immediately confirmed, but usually they go into a pile for later observation. There's currently over 5000 candidates that somebody will need to eventually follow up on. And then, roughly 1% of the confirmed ones wind up being in the habitable zones of their stars.

Confirming candidates, which involves targeted observations of candidates to try and establish their parameters.

Different missions have different goals with regards to the above, which is part of why there's so much variation over time. A mission to confirm specific candidates isn't likely to add to the pile of new candidates, but might add a small number of confirmations.

You are right @ScottEastman that James Web Telescope could be useful in that regard (ESA website about exoplanets search lists it among the tools for this mission), but as @jrl mentioned only 1,24% of all exoplanets in the data we have are listed as potentially habitable. So James Web Telescope would have to increase its discovery rate a lot. I am not saying that is impossible, but without the information that it is changing its focus to that goal, I don't think we have a basis to update based on it. @jrl thank you for the insight about the 5000 candidates. Do you by chance know how many candidates are still there among data collected by Kepler?

Interacting with our spouses for relevant information is great 😀. But truth is, the stuff about Kepler's contributions were largely included in the "Discussion and analysis" part of my rationale below:

The relatively high numbers of yearly discoveries between 2013 and 2017 can be largely attributed to the Kepler space telescope, launched in 2009 and retired on Oct 2018, which had the detection of exoplanets as its primary mission. Although new exoplanets have been discovered from Kepler data as recently as 2023, its last contribution to the habitable worlds catalog were 2 exoplanets in 2020 (Kepler-1701 b and Kepler-1649 c).

In fact, the contributions of Kepler are even higher than your table implies, since 'K2' is just the name of Kepler's "extended" mission (2014-2018); in other words, sensor-wise, K2 is Kepler: https://science.nasa.gov/mission/kepler/ (K2 was not actually a time extension, just a renaming of the mission after Kepler lost a gyroscope in May 2013 and engineers managed to come up with a solution to save it).

Having this detail clarified reveals that the "long tail" of Kepler data is even more impressive and astonishing: anything labeled as "Kepler" in the files comes from data that were actually collected before May 2013 (the date when the 2nd gyro failed and data collection was disabled), including the high outlier numbers of 2014 & 2016, Kepler's "third-best year" (2021), and the 70 exoplanets confirmed in 2023! In fact, we had a data collection gap of more than 1 year, since K2 became operational only in June 2014.

Chronologically speaking, TESS went into operation the same year Kepler/K2 was retired (2018). The slight discrepancy between the number of exoplanets discovered by it in your table (415) and in my rationale below (420) is due to the 5 exoplanets confirmed by TESS in 2024 (ask for 2024 in 'Discovery Year" here). This gives us an indirect, and perhaps useful, hint: despite our resolution source having been reportedly last updated on Feb 1, it evidently does not include (yet) exoplanets discovered in January 2024., i.e the absence from the excel file of any discoveries in 2024 is due to an actual lack of update, and not to a lack of confirmed discoveries.

What your table nicely reveals is that, in a problem where we seem to have difficulty discerning clear and persisting trends, TESS rate of discovery seems to be steadily increasing indeed! But again, this is only about the total number, and not the habitables one (will look into it further, but TESS was responsible for the sole habitable detection of 2021...)

2021 was still the third-best year for Kepler

This in fact illustrates nicely what I and @Tolga have already observed about the practically non-existent correlation between the numbers of total exoplanets and habitable ones: despite being the 3rd-highest year for Kepler, 2021 has been so far the worst year for habitable worlds detected: only 1 planet (not even by Kepler, but by TESS), which can easily be considered a low-range outlier.

we should not expect numbers like in 2014 or 2016 from [Kepler]

We should definitely not, but again, speaking about the quantity of interest here (habitable worlds), we don't need the high numbers that were registered in those years (8 and 11 respectively) - a mere number of 5 will be enough to resolve this as Yes. And even if we subtract the last contributions of Kepler/K2 (2 habitable worlds among the 10 registered in 2020), we are still well above the required threshold for that year. We reached the threshold of 5 in 2022 and 2023 without any contribution from Kepler/K2.

Base rates and Laplace rule are useful for forecasting, but if the causal mechanics/driving forces behind the numbers change, our expectations should also change.

You are of course very right! Thing is, gaining the necessary familiarity with the specifics and the significant details of a forecasting problem in order to (hopefully begin to) understand such causal mechanisms and driving forces takes time (and collaboration!), and it can seldom (if ever) be assumed from the 1st (or 2nd...) sitting. That's why the base rates are only a start, and never the end, of the forecasting process.

The James Webb telescope has discovered 2 exoplanets

These are actually still candidates; as @jrl says, there is a standard procedure for an exoplanet to go from candidate to confirmed status. Fact is, as @HarrisonD has reported below (and I have confirmed myself), the JWST has so far contributed one single confirmed exoplanet in May 2023, and it is not a habitable one (neither are the new candidates, it would seem).

Do you by chance know how many candidates are still there among data collected by Kepler?

It seems we can get the official numbers. From the links here, go to 'KOI Table" (either entry, they both give the same result) and put CANDIDATE in the field 'Exoplanet Archive Disposition'; it gives 1983 records. Notice that this number is about Kepler proper (i.e. data before May 2013), and it does not include K2 (data from June 2014 to October 2018). For K2, go to K2 Planets and Candidates Table from the same page, and ask again for CANDIDATE in the 'Archive Disposition' field; it gives 1370 records. So, it would seem that we still have 3353 candidate exoplanets waiting to be confirmed (or not) from the Kepler/K2 data alone; if we accept a rough estimation of ~5000 current candidates (have not managed to get the exact number from the NASA archive, as asking for Candidate in the Solution Type includes candidates that have been subsequently confirmed), it means that, as of Feb 2024, ~67% of the candidates are still due to Kepler/K2.

JWST's primary mission is cosmology, so they're not actively seeking exoplanets, and any that are discovered are probably just by chance.

This was my initial impression, too. But as already commented below, the study of exoplanets is included explicitly in its main mission objectives. What this means for discovery of new ones is less clear, but again, this is not of relevance for the question here, as it seems very reasonable that the further study of confirmed exoplanets can provide data for inclusion to the habitable list, which, after all, is what we actually care about here...

So, I looked deeper at the data, and as I suspected in my previous comment (and my wife knew it already) behind the outlier results in 2014 and 2016 was one specific mission: Kepler space telescope. Kepler was responsible for the discovery of 90% of exoplanets discovered in 2014 and 85% of the discoveries made in the record year 2016. It was also responsible for 49,9% of discoveries of exoplanets in the dataset.

What is important, Kepler was retired by NASA on October 30, 2018 after it ran out of fuel. In the dataset, we can still see discoveries of exoplanets attributed to Kepler after 2018 - even last year (70 discoveries, we can say it was a good year for Kepler), but the numbers are lower now (2021 was still the third-best year for Kepler) with an irregular downward trend. I assume that the discoveries were made in later years based on the analysis of images previously collected by Kepler.

Its mission is continued by Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) since 2018, but it was not that effective as Kepler, but it seems to be getting better over the years. See my table below with the most efficient projects/observatories over the years. Relative formatting is applied to each row to show changes over time.

Kepler might still be a source of a substantial number of discoveries of exoplanets this year (last year it was 70), or it may bring little to the total number (in 2022 it was 4), but we should not expect numbers like in 2014 or 2016 from it. Based on that, I am further reducing my probability slightly to 56%.

My thoughts: Base rates and Laplace rule are useful for forecasting, but if the causal mechanics/driving forces behind the numbers change, our expectations should also change. But this correction, of course, becomes subjective, and may make us even more vulnerable to the influence of biases. See a great comment about that by @ctsats : https://www.infer-pub.com/comments/121097

@ctsats @WeirdAwkward @DimaKlenchin @ScottEastman @probahilliby @MrLittleTexas @BlancaElenaGG @Tolga

@michal_dubrawski The James Webb telescope has discovered 2 exoplanets. This is a very small number but its unique abilities could be trained on the currently known exoplanets with the greatest likelihood of potential habitability. https://www.space.com/james-webb-space-telescope-exoplanets-dead-stars#

Bear in mind there's two operations involved in finding exoplanets:

Different missions have different goals with regards to the above, which is part of why there's so much variation over time. A mission to confirm specific candidates isn't likely to add to the pile of new candidates, but might add a small number of confirmations.

@jrl thank you for the insight about the 5000 candidates. Do you by chance know how many candidates are still there among data collected by Kepler?

Re number of candidates, I think that's an overall list across all observatories. There's some data on Wikipedia, but not sure if it is kept current.

JWST's primary mission is cosmology, so they're not actively seeking exoplanets, and any that are discovered are probably just by chance.

Thanks Michał. Just some secondary remarks.

Interacting with our spouses for relevant information is great 😀. But truth is, the stuff about Kepler's contributions were largely included in the "Discussion and analysis" part of my rationale below:

In fact, the contributions of Kepler are even higher than your table implies, since 'K2' is just the name of Kepler's "extended" mission (2014-2018); in other words, sensor-wise, K2 is Kepler: https://science.nasa.gov/mission/kepler/ (K2 was not actually a time extension, just a renaming of the mission after Kepler lost a gyroscope in May 2013 and engineers managed to come up with a solution to save it).

Having this detail clarified reveals that the "long tail" of Kepler data is even more impressive and astonishing: anything labeled as "Kepler" in the files comes from data that were actually collected before May 2013 (the date when the 2nd gyro failed and data collection was disabled), including the high outlier numbers of 2014 & 2016, Kepler's "third-best year" (2021), and the 70 exoplanets confirmed in 2023! In fact, we had a data collection gap of more than 1 year, since K2 became operational only in June 2014.

Chronologically speaking, TESS went into operation the same year Kepler/K2 was retired (2018). The slight discrepancy between the number of exoplanets discovered by it in your table (415) and in my rationale below (420) is due to the 5 exoplanets confirmed by TESS in 2024 (ask for 2024 in 'Discovery Year" here). This gives us an indirect, and perhaps useful, hint: despite our resolution source having been reportedly last updated on Feb 1, it evidently does not include (yet) exoplanets discovered in January 2024., i.e the absence from the excel file of any discoveries in 2024 is due to an actual lack of update, and not to a lack of confirmed discoveries.

What your table nicely reveals is that, in a problem where we seem to have difficulty discerning clear and persisting trends, TESS rate of discovery seems to be steadily increasing indeed! But again, this is only about the total number, and not the habitables one (will look into it further, but TESS was responsible for the sole habitable detection of 2021...)

This in fact illustrates nicely what I and @Tolga have already observed about the practically non-existent correlation between the numbers of total exoplanets and habitable ones: despite being the 3rd-highest year for Kepler, 2021 has been so far the worst year for habitable worlds detected: only 1 planet (not even by Kepler, but by TESS), which can easily be considered a low-range outlier.

We should definitely not, but again, speaking about the quantity of interest here (habitable worlds), we don't need the high numbers that were registered in those years (8 and 11 respectively) - a mere number of 5 will be enough to resolve this as Yes. And even if we subtract the last contributions of Kepler/K2 (2 habitable worlds among the 10 registered in 2020), we are still well above the required threshold for that year. We reached the threshold of 5 in 2022 and 2023 without any contribution from Kepler/K2.

You are of course very right! Thing is, gaining the necessary familiarity with the specifics and the significant details of a forecasting problem in order to (hopefully begin to) understand such causal mechanisms and driving forces takes time (and collaboration!), and it can seldom (if ever) be assumed from the 1st (or 2nd...) sitting. That's why the base rates are only a start, and never the end, of the forecasting process.

PS And yes, just as I was ready to press "submit", the clarification I had requested was published, moving the resolution date to Jan 31, 2025 (or even later): https://www.infer-pub.com/questions/1373-will-at-least-five-more-exoplanets-be-found-to-be-potentially-habitable-between-1-february-2024-and-31-december-2024/clarifications

@ScottEastman

These are actually still candidates; as @jrl says, there is a standard procedure for an exoplanet to go from candidate to confirmed status. Fact is, as @HarrisonD has reported below (and I have confirmed myself), the JWST has so far contributed one single confirmed exoplanet in May 2023, and it is not a habitable one (neither are the new candidates, it would seem).

back to @michal_dubrawski

It seems we can get the official numbers. From the links here, go to 'KOI Table" (either entry, they both give the same result) and put CANDIDATE in the field 'Exoplanet Archive Disposition'; it gives 1983 records. Notice that this number is about Kepler proper (i.e. data before May 2013), and it does not include K2 (data from June 2014 to October 2018). For K2, go to K2 Planets and Candidates Table from the same page, and ask again for CANDIDATE in the 'Archive Disposition' field; it gives 1370 records. So, it would seem that we still have 3353 candidate exoplanets waiting to be confirmed (or not) from the Kepler/K2 data alone; if we accept a rough estimation of ~5000 current candidates (have not managed to get the exact number from the NASA archive, as asking for Candidate in the Solution Type includes candidates that have been subsequently confirmed), it means that, as of Feb 2024, ~67% of the candidates are still due to Kepler/K2.

@jrl

This was my initial impression, too. But as already commented below, the study of exoplanets is included explicitly in its main mission objectives. What this means for discovery of new ones is less clear, but again, this is not of relevance for the question here, as it seems very reasonable that the further study of confirmed exoplanets can provide data for inclusion to the habitable list, which, after all, is what we actually care about here...